International Reparation Initiative for Conflict-Related Sexual Violence: Four Challenges

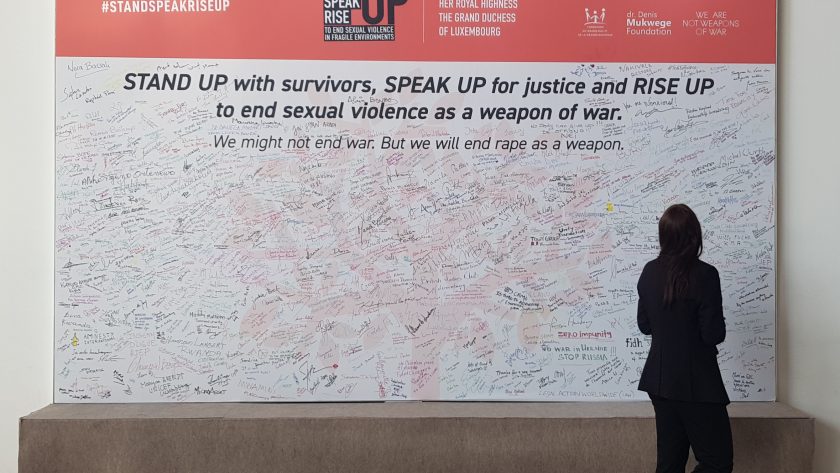

Following the award of the Nobel Peace prize to Dr Denis Mukwege and Nadia Murad in December 2018, there is a substantial effort to capitalise on the publicity by pressing for an ‘International Reparation Initiative’ for victims of conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV). In Luxembourg this week high level actors, donors, and victim-survivors of CRSV will converge for the ‘Stand Speak Rise Up’ to ‘end rape as a weapon’.

There is no doubt that conflict-related sexual violence is an insidious atrocity too commonly committed in conflicts throughout the world, often hidden as remains the case in Northern Ireland, causing serious physical, psychological and sexual health complications for victims, and intentionally rupturing familial and communal bonds. While an incredibly significant issue that needs to be tackled in a comprehensive and joined up effort, it raises some issues for international law.

The UK government’s initiative to end rape in war through its 2014 ‘End Sexual Violence in War’ summit, proposed a protocol for the investigation and prosecution of conflict-related sexual violence. However it was criticised as a ‘costly failure’ with many donors and experts pulling their support, never mind the UK government’s expenditure of £5.2 million on the summit, more than its annual budget to tackle conflict-related sexual violence.

At the International Criminal Court and Extraordinary African Chambers, while there have been considerable efforts by victims and civil society to claim reparations for sexual violence, there has yet to be a judgment to this effect. The past five years have shown little legal results, with cases collapsing or acquittals in the Kenyatta, Bemba and Gbagbo at the ICC, which all included charges of rape, of which Habré was acquitted at the EAC. In particular the collapse of the Bemba trial last year and reports by experts and other participants on reparations, highlighted the need for timely and effective reparations which go beyond compensation.

It is not the first time that reparations for CRSV have been systematically recommended. The 2007 Nairobi Declaration proposed a more transformational agenda for reparations for sexual violence beyond restitution, compensation and rehabilitation to also tackle political and structural inequalities that negatively shape women’s and girl’s lives. The Mukwege Foundation is suggesting a more aspiring ‘International Reparations Initiative’ to ‘recognise individuals and groups as victims, and provide assistance’ consisting of a fund that can award compensation, with an international and local committees to determine allocation and forms of reparation. There are four challenges of delivering such an ambitious reparations: eligibility; international focus; funding; and whether it is assistance or reparation.

Eligibility

Reparations involve selectivity, prioritising some harm over others given limited resources and a large universe of victims. This often has political undertones, but also poses evidential challenges in proving claims and harms. In Colombia victims of CRSV committed by state, paramilitary and guerrilla actors can access reparations through the Victims’ Unit, but female members of armed groups who were subjected to forced abortions and sexual violence are denied recognition and reparations. In Uganda, northern parliamentarians have recently passed a resolution for the government to provide financial support for former sexual slaves and children born of war by the Lord’s Resistance Army. While such initiatives are to be welcomed, without inclusive recognition of individuals based on harm, rather than actor, it means that in the Ugandan context victims of government sexual violence, in particular against men and boys is neglected.

International focus

While it is welcomed that international attention is concentrated to better tackle CRSV, the experience of transitional justice and human rights practice on reparations counsels modesty. Victims do not need their expectations gratuitously raised. The 2014 London summit promised to end rape in conflict, and the Luxembourg conflict promises something similar, yet no amount of reparations is unlikely to change this alone. The international focus and concentration of resources from the top-down, can disrupt the capacity and more quiet work carried out by local organisation funded by international partners. In Colombia we recently found that some victims in rural areas were more inclined to go to more neutral health providers (such as the ICRC) than the state health providers, due to their infiltration by paramilitary and guerrilla groups. How will an international body navigate a new domestic context, especially during ongoing insecurity, have the capacity to deliver money to victims or for them to claim such redress? The ICC Trust Fund continues to face these problems in implementing reparations in the DRC and Mali, as well as its assistance programme in CAR. Local committees may balance the international nature of the initiative, but how does this fit into the well-established human rights and more recently international criminal law jurisprudence on victim participation and their rights.

Funding

How will an international fund attract enough financial resources to support potentially thousands, if not hundreds of thousands of victims? Will such a fund compete with the ICC Trust Fund for Victims or work by other organisations, such as MSF or the ICRC, which have a long track record of providing medical rehabilitation to victims of CRSV? In terms of funding through a trust fund, former UN Special Rapporteur on truth, justice, reparations and guarantees of non-recurrence Pablo de Greiff notes that countries which establish trust funds to resource reparations are far less successful in delivering effective measures than governments who dedicate a budget line, the distinction of political will separating the two. This is apparent in Sierra Leone and Nepal, where the reparation programmes were based on trust funds to be contributed by the government and donors, which only saw a fraction funded in first couple of years.

The weakness of trust funds to marshal sufficient funds is not limited to domestic funds, but is also evident for international victim funds. The UN Voluntary Fund for Victims of Torture needs $12 million to annually operate, but receives substantially less than this, as it is dependent on fundraising and voluntary contributions. Similarly the Trust Fund for Victims at the International Criminal Court has seen a marked reduction in contributions from State Parties of €5 million per annum to now €2.7 million, despite planning to raise €40 million by 2021 to meet the increasing pressures to deliver reparations in a growing number of cases. Accordingly donor voluntary contributions to trust funds to establish and fund reparation programmes are unlikely to have long term success in dispensing substantive reparations to victims.

This speaks to a broader issue of financial commitment to addressing the plight of victims of international crimes. That while hundreds of millions is spent on international courts, mainly on facilities and staff costs, very little reaches those most affected by such crimes. This is not to detract from the professionalism or important work these bodies generally do, but as the UK delegation to the ICC Assembly of State Parties highlighted in December, the expenditure of €1.5 billion for only three convictions, is a poor return. Can an international body fare any better?

Assistance or Reparations?

At the heart of the proposed International Reparation Initiative (IRI) is the use of the word ‘reparations’, which in international law and human rights connotes a secondary obligation of a responsible actor to remedy their breach of a primary obligation. In other words, those who commit gross violations of human rights or international crimes are obligated to provide reparations for the harm caused.

The Initiative seems to be a step back from the 2007 Nairobi Declaration, which emphasises the responsibility of the national government to provide reparations. The UN Basic Principles on Reparations similarly support this point, even when non-state actors commit violations, the state remains responsible to ensure every person’s right to a remedy within its jurisdiction. Having an international body to hear claims and adjudicate with responsible actors beyond regional human rights courts, may be an alternative avenue. Yet having an International Reparations Initiative that provide symbolic recognition to victims and compensation, may feel more like charity or assistance, something which the ‘comfort women’ in Korea have adamantly fought against, instead demanding the Japanese government to take responsibility for its army’s past actions. There is a risk that the IRI may dilute victims’ rights to reparations, by placating them with assistance measures, rather than responsible actors being made to face their legal obligations and remedy the harm they have caused.

These challenges may be fundamental to the long-term sustainability of the IRI. However it may be that we need a more articulated and complex vision of how reparations for conflict-related sexual violence can be delivered, through interim relief to more long term reparations by states or other responsible actors. A better coordinated approach to CRSV that connects and complements ongoing work on the ground and international level would be a good start. That all said by focusing on CRSV, we are in a way creating a hierarchy of victims for international attention for reparations, leaving behind other victims of serious violations such as torture, serious injury, disappearance and genocide to name a few.

This blog originally appeared on Opinio Juris.